Four Hands on One Pulse

A Dialogue Across Traditions

Four Hands on One Pulse: A Dialogue Across Traditions

"Living people are warm, corpses are cold, and as humans age their bodies become cooler, easily chilled. Since Plato’s Timaeus, at least, Greek reflections on vitality saw special significance in the ties between life and warmth. Preserving life required stoking a sort of internal physiological fire, maintaining what Aristotle termed innate heat. Food provided the essential fuel; without it, the fire would die. For the well-nourished, however, the more pressing threat was the opposite. Until one grew old and the innate heat waned, a person needed constant refrigeration to keep from burning up. This was one reason why one had to breathe to live." - Shigehisa Kurkiyama, Blood and Life, The Expressiveness of the Body, p. 230

A Short Story

Preface:

This story grew out of my reading of ‘The Expressiveness of the Body’ by Shigehisa Kuriyama—a book given to me by Michael Broffman of the Pine Street Clinic. I had shared with Michael a course description Profess Kuriyama is going to give this fall through the Harvard Extension Program:

I’m considering enrolling in, and in return, he handed me this book.

Reading it opened my eyes to how different cultures, for centuries, have listened to the body in their own distinct ways. What struck me most wasn’t just the contrast between East and West, but how each tradition developed its own language for reading the body—not just through machines or anatomy, but through the hand, the breath, rhythm, and intuition.

That led me to wonder: what if four doctors, each from a different tradition, examined the same patient at the same time? What would they see? What would they hear—or feel? Would they agree, or would their lenses show entirely different pictures?

This story is an imaginative response to that question. While fictional, it’s grounded in real practices and real ways of knowing. It’s meant not to draw conclusions, but to reflect the mystery and richness that comes when we allow the body to speak—and when we truly learn to listen.

Setting:

A modest community wellness clinic in a small town—modern, but with a quiet meditation garden outside. The four doctors are gathered for a collaborative case demonstration, meant to foster cross-traditional dialogue and showcase how different healing systems interpret the same patient.

Characters:

Samuel Lin – a mid-50s carpenter, patient

Dr. Mei Chen – Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) physician, Beijing-trained

Dr. Haru Tanaka – Japanese Kampo physician, Kyoto-trained

Dr. Alicia Reyes – Harvard-trained M.D., post-doc in Integrative East-West medicine

Dr. Ananya Rao – Ayurvedic Vaidya, Kerala lineage

Four Hands on One Pulse: A Dialogue Across Traditions

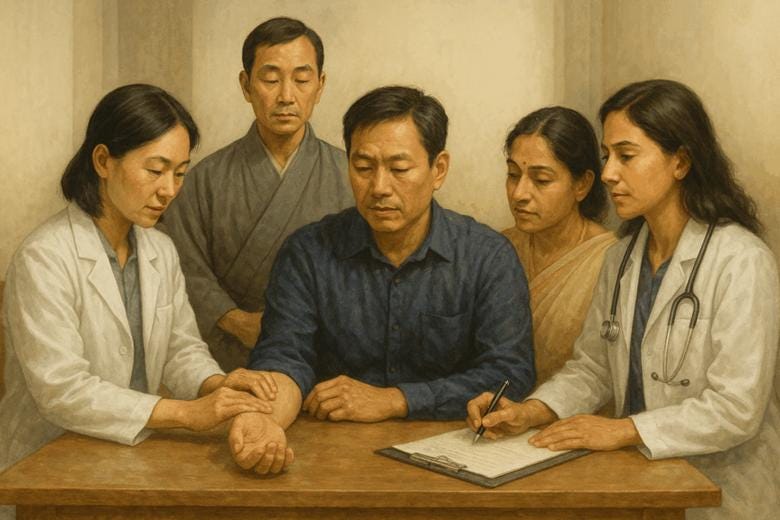

The Arrival

Samuel Lin sat nervously in the small examination room, his eyes darting between the four doctors arranged in a semi-circle before him. He’d come to the Integrative Medicine Center seeking answers for the dull ache behind his sternum that had plagued him for weeks. What he hadn’t expected was to become the subject of an impromptu demonstration of comparative diagnostic techniques.

The Chinese Pulse

Dr. Mei Chen, a practitioner of Traditional Chinese Medicine, spoke first. “Mr. Lin, we’re going to conduct a joint examination today. The only rule is that you must not describe your symptoms aloud. Your body will speak for you.”

Samuel nodded, uncertain. He watched as Dr. Chen approached, her movements graceful and deliberate. She placed three fingers along his left wrist—cun, guan, chi—her touch light but assured. After a moment, she spoke softly in Mandarin, then English:

“Your pulse is tense and unyielding, like a taut string. There’s anger held in, frustration pushing upward from the liver and binding the chest. Qi is not circulating—it’s stuck.”

She paused, reflecting.

“This pattern—Liver Qi stagnation with rebellious Qi rising—may lead to tightness, shallow breathing, chest fullness. Possibly accompanied by sighing, irritability, even headaches. We must course the Qi, resolve constraint, and harmonize the Shaoyang.”

She jotted down a prescription: Xiao Chai Hu Tang, with gentle cupping between the scapulae, and recommended walks at dusk.

Samuel blinked, recalling last night’s heated argument with his foreman. How could she know.

The Japanese Pulse

Next came Dr. Haru Tanaka, a Kampo physician from Kyoto. His touch was feather-light, barely grazing Samuel’s skin as his fingers danced along the radial artery. His eyes stayed lowered, as if reading script beneath the skin.

“The pulse is soft on the surface, absent beneath. It comes and goes—a reflection of kyo—deficiency. The blood is thin, and what rises is not rooted.”

He looked at the others and continued:

“Heat lingers above—perhaps mild insomnia or warm sensations in the chest—but below is cold. He lacks circulating power. I prescribe Keishibukuryogan to warm the blood and remove stasis.”

He sketched a diet plan emphasizing warm rice gruel with shiso leaf, gentle soups, and no raw vegetables.

Samuel’s stomach rumbled at the thought.

The Biomedical Interface

Dr. Alicia Reyes stepped forward next. A Harvard-trained M.D. studying integrative medicine, she fastened a digital sphygmograph to Samuel’s wrist while keeping two fingers beneath the cuff.

“Your pulse has a subtle irregularity—every fifth beat is premature. It’s likely benign, but we call this a premature ventricular contraction, or PVC. Combined with low amplitude, it points to possible stress, autonomic imbalance, or minor heart qi deficiency in TCM terms.”

She typed notes quickly.

“From a Western perspective: monitor with an EKG, rule out electrolyte or thyroid imbalances. From a Chinese overlay: consider Dan Shen Yin to move blood and calm the spirit.”

She smiled.

“And tai chi—twice a week. Let rhythm return through movement.”

Samuel nodded, the fusion of science and spirit oddly comforting.

The Ayurvedic Reading

Finally, Dr. Ananya Rao approached. The Ayurvedic vaidya from Kerala closed her eyes as she placed three fingers on Samuel’s pulse points, seeming to listen with her entire being.

“His pulse is fluttery—vata rising. Dry, irregular, and fast. But there’s a faint heat underneath—pitta—which dries further what little nourishment remains.”

She looked up at Samuel.

“You carry wind in the chest. Restless thoughts have disturbed your heart, agitated your mind, and weakened your digestion. This ache is not just physical—it’s a dry fire without oil, burning into your chest.”

Her prescription was holistic:

An herbal decoction of Ashwagandha, Arjuna, and Guduchi to strengthen the heart and calm vata-pitta.

A vata-soothing diet: warm, oily foods—root vegetables, ghee, and spiced lentils.

Daily abhyanga (warm sesame oil massage) and shirodhara (oil drip over the forehead).

Breathwork: Nadi Shodhana (alternate nostril breathing).

“Rise before sunrise. Eat your main meal at noon. Sleep early. Rhythm is your medicine.”

Dialogue in the Garden

The four doctors gathered in the clinic’s garden over cups of herbal tea. Samuel sat nearby, reflecting quietly.

Dr. Chen spoke first.

“When the liver’s qi is bound, emotion builds in the chest. The body tightens. The mind follows.”

Dr. Tanaka added, sipping his tea.

“But if the blood is weak, it cannot anchor emotion. The heart floats, lost in heat.”

Dr. Reyes leaned forward.

“And we see it in the beat—the skipped rhythm, the low perfusion. Stress affects the heart, even in Western terms. But we lack the poetry to say it well.”

Dr. Rao closed her eyes for a moment.

“In Ayurveda, the heart is not just an organ. It is the seat of consciousness. Aches of the chest are rarely just muscular. They are the soul’s attempt to speak.”

They paused. Each had seen something different. Each had been right.

Samuel’s Reflection

Samuel stood alone in the garden, hand on chest. He breathed deeply. The ache remained, but it felt…witnessed.

He thought: One heard qi bound by emotion. Another felt blood too thin to root the heart. A third saw a mechanical skip, and the fourth described wind in his soul.

He smiled.

Maybe the pain had been waiting to be heard—not by one, but by all.

Epilogue

Back in the room, he turned to the doctors.

“So… which of you is right?”

Dr. Chen shook her head gently. “That is not the question.”

Dr. Tanaka: “Each of us sees with different eyes.”

Dr. Reyes: “And listens with different instruments.”

Dr. Rao: “A wise healer learns to listen to them all.”

Samuel nodded. He didn’t yet have a cure. But he had something better: understanding. Four kinds of it, woven like threads of breath across his wrist.

Dedicated to the practitioners who listen—not just to symptoms, but to the silent languages of the body.